Maximum Heart Rate

By: Tim Smith

A year ago my old running watch gave up the ghost and so I was in the market for a new wrist chronometer. What do I want out of a watch? I like to know how far I have run and am I late for dinner. I'll confess that sometimes it is nice to also have that "stopwatch" feature; I like to know my race times and my splits during intervals. And once a watch could measure time and distance, and since it has a small computer, it of course would want to display pace. But I try not to obsess with my watch.

However, you can't get a simple watch like that anymore.

Watches today want to also measure your heart rate, and some will even measure your blood oxygen level and number of steps. They also like to report to you things like calories burned, heart rates zone, and so forth. It is a bit overwhelming, and I am not going to try and understand all of these things right now.

So for months I wore my watch, noted times and distances, and ignored everything else. But one day, after running a time trial this summer, I noted that I had run at "98% of my maximum heart rate". It actually had not felt that hard, but it got me thinking, "What does it think my maximum heart rate is? And why does it think that?"

It turns out that most watches use the simple equation;

max heart rate = 220 - age

As some of you may know I am a physics professor, and after having graded 10,000 homework sets (or so it seems) I would take off points because the units of that equation just can't be right. "Max heart rate" is in "beats per minute", age is in years, and 220 is just a number. What the equation should be is;

max heart rate [beats/min] = 220 [beats/min] - age [year] * constant

where that constant is:

constant = 1.00 [beats/min]/[year],

which is startling. Nothing in the universe is exactly 1.00, especially with those odd units [beats/min]/[years]. In other words, this is a convenient equation, but I am skeptical about it being a precise equation. But it is also so widely used that it can't be completely wrong.

Other Equations

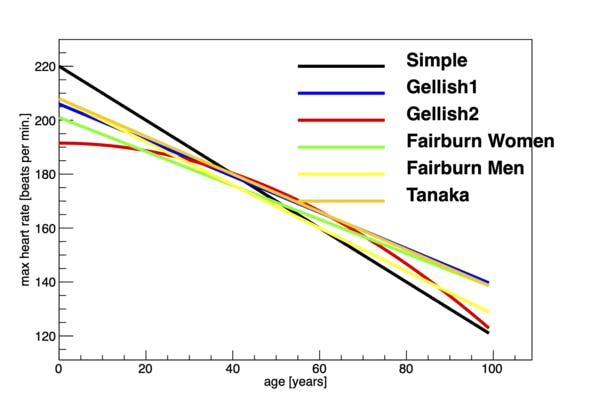

A quick search of the internet, and especially an article in Runner's World, turned up a number of alternative equations for maximum heart rate as a function of age.

When I see a plot like this it makes me pause. All of these lines report the same thing, yet there is an obvious range of results. Presumably a number of different researchers collected a bunch of people and gave them rigorous max-heart-rate tests. They then plotted their measurements and tried to pass a simple line through the data. I expect that they may have collected their participants differently, or even used slightly different protocols in their lab test. But I think the real take-away is that the equations are not a rigid line. Your maximum heart rate may vary by 10 beats or so from any particular equation.

So lets say I really am into heart-beat-rate training and I need to know my maximum. How do I get it, if not from an equation? There are two broad techniques for obtaining it; a "lab" (treadmill) measurement, and a "field" measurement.

Lab measurement

I talked with Laura Hagley about this and she told me that lab measurements were the bread and butter of her school work when studying health physiology. Max-heart-rate and VO2-max are tied together and usually they are measured at the same time. You do a stress test on a treadmill and measure both VO2 and heart-rate until you can go no further.

The stress test puts a runner on a treadmill and then incrementally increases the speed and grade of the treadmill. Laura told me that there are various protocols for how long you spend at each speed/grade before upping the stress. But that there are a few key things

- You need to start out slow enough that the athlete has time to warm up before hitting that ultimate stress level.

- You want each stage to be long enough, a few minutes, such that the heart and breathing rates have come to an equilibrium.

- You do not want so many small steps and stages that the body is out of fuel before you get to that ultimate stress level.

I have recently read George Sheehan's description of one of these tests from the 1970's. Laura's description sounded a bit more humane. It is still an ultimate effort test, but not the laboratory inflicted torture that Sheehan described,

"A mounting wave of fatigue and pain went over my body. My chest and legs were in a relentlessly closing vice. More people had wandered in to watch my final agony. . . . But the struggle between me and the machine was coming to a close.

"I had waited too long. I was finished and still had thirty seconds and 130 yards to go on this infernal, unforgiving apparatus. It was an eternity in time, and infinity in space. . . . four, three, two, one. The treadmill stopped.

"I had peaked and gone down the other side, reached my maximum and gone past it. I had done what they wanted me to do. The pain had receded. I sprawled out on a chair, content, trying to think of an equivalent maximum human performance.

"'How soon,' I asked, `can I see the baby?'"

From Laura's description I get the feeling that the modern measurements would like to push you to that same level, but also leave you un-scarred and able to still run the next day.

Field Measurement

I recently had a zoom session with Pam Crandall. Pam is a long time member of UVRC and a private fitness coach. I asked her about "Field Test", and how she uses heart rate data in her training.

Pam described a method in which you go out running on the roads and ramp up your pace over a number of miles. Unlike the lab test, there are no breathing tubes and face mask. It is just you and your heart rate monitor.

I described to her Jack Daniel's description of two field test protocols. One involved hills. But the second was to ramp up in 15 to 20 minutes. I asked her how that differed from a race. Pam smiled at me and said, "You see a race in a field test? That is because you are a 5k guy." I think Pam knows me better than I realized.

The long and the short is that if you are running a 5k race, one that you really care about, a championship, then near the end you should be at about your maximum heart rate.

But you SHOULD NOT run championship level efforts too often. You can only do that a few times a season.

How to Use

So once you have established your maximum heart rate, how do you put that number to work?

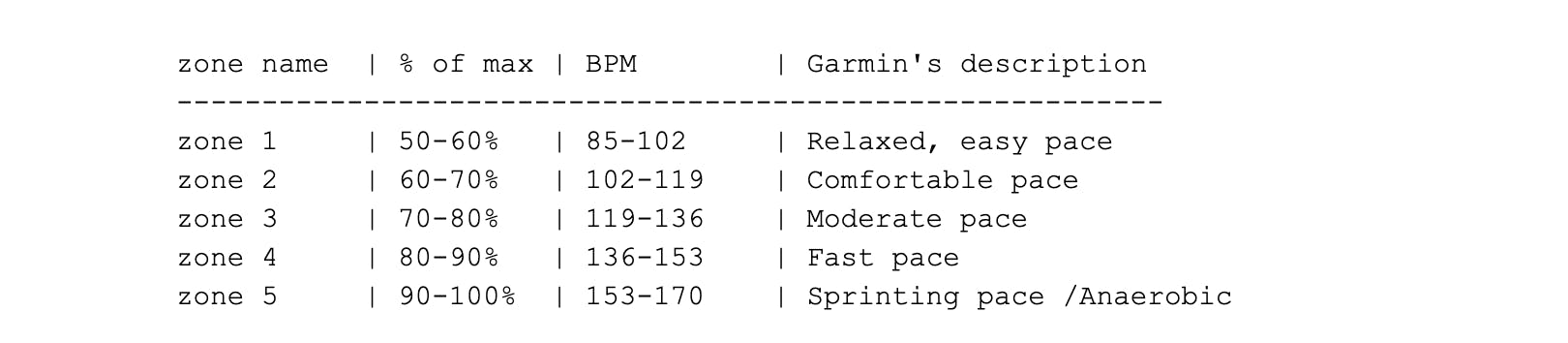

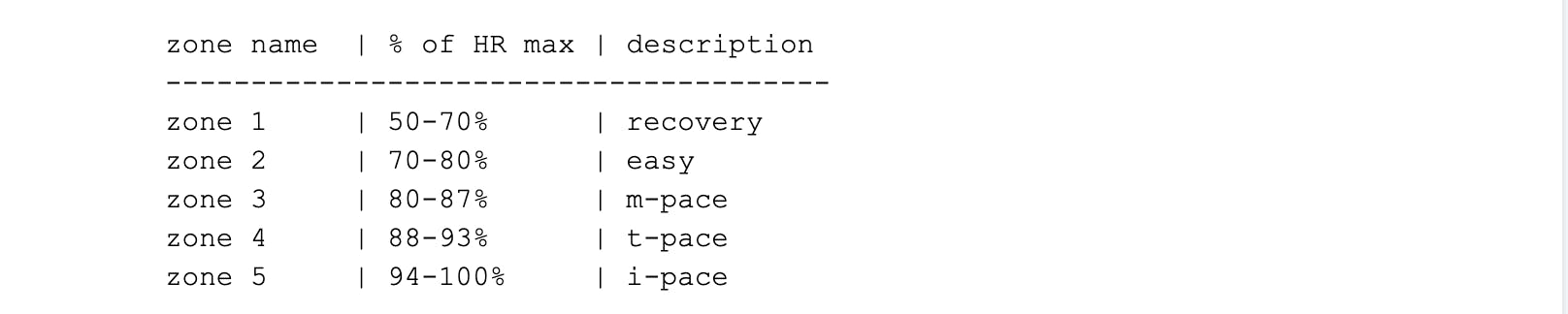

In heart rate training people talk about different "zones". Zones are defined as a range of heart rates expressed as a percentage of maximum. Let's say that somehow I have established that my maximum heart rate is 170 beats per minute (BPM). Then my zones are

(this is the scale used a Garmin devices)

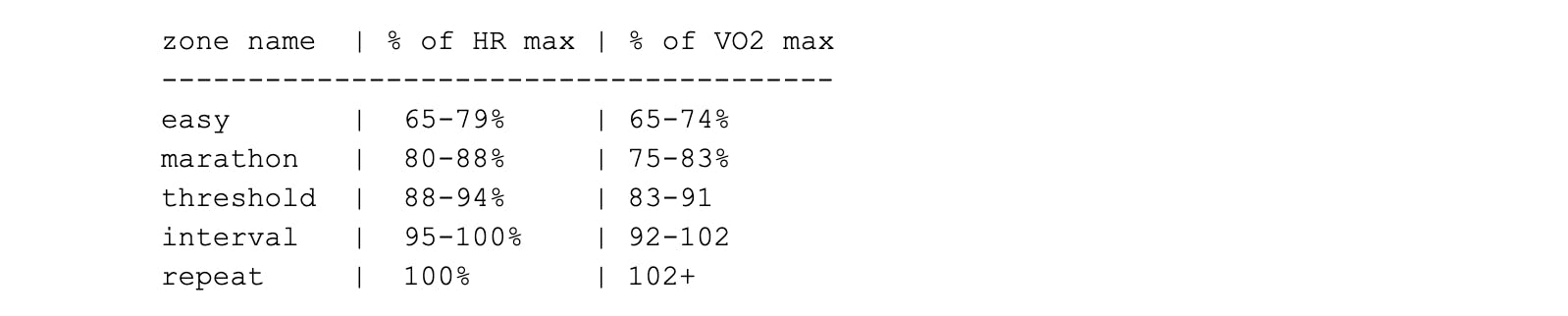

We can also relate this to the % VO2 max scale associated with Jack Daniels that I have described in the past. Then:

I have also seen a hybrid scale which uses the names of the first, but the division much like the second.

Yes there are many scales out there, so pay attention to your source. Your watch and your coaching book may not match, but you can figure it out.

The way you use this is to think through your work out ahead of time. "I am doing a threshold work out, tempo pace, which means my watch should tell me high zone 4". Or, "Today is a recovery day, I should never get above zone 2." Then you just keep the number 4 or 2 in your head.

Heart Rate Drift & Drops

If you are using heart rate, it is important to understand some of the nuances. Otherwise good, but mis-understood, data might lead you down the wrong training path. So let's say you are running a pretty hard hour long run. Your heart rate increases for a while and then settles into a steady-state. Breathing, pace and heart-rate are all aligned. However, after awhile, your heart-rate starts to creep up, or "drift". Your pace is steady, your breathing rate is the same, but your heart rate climbs. So what's going on? If you are tied to a heart rate regiment, should you slow down to get your heart back on target?

What is happening is that the core of your body is getting hot, so your body is diverting some of your blood to your skin to help cool you off. But if 10% of your blood is not heading to your legs, your heart needs to pump more blood, and so beats more often.

But you are not breathing harder, which seems at first counter intuitive. This is because the blood going to your skin is dumping heat, but not using the oxygen. That blood, next time it passes through your lungs is already oxygen rich. In this case your breathing rate is probably a better indication of energy burned than heart rate.

So what pace to run this work out? You were probably aiming for steady effort and not steady heart rate. So you need to hold your pace and breathing rate, and just learn to recognize heart rate drift.

Unless it is downward.

A downward drift probably doesn't mean cooling (if it does you will have noticed the icicles from your nose). Rather it means the body really has gone into fatigue. And unless the finish line is in sight, you are probably going to have to adjust somehow.

In Conclusion

When talking with both Laura and Pam, I asked them, “What did they think of heart rate training, and how do they use it?” Both of them told me essentially, "Yes it is great", but also, "But I don't use it too much."

Pam told me a story about when she first started using heart rate info. One day after a tough interval workout she was going over her data with her coach. The pace, heart rate and effort just didn't seem to match. Pam's coach then told her that he had made a mistake in assigning that work-out. She clearly needed some recovery time, and should not have beans slavish to the monitor.

However, the heart rate monitor did help her understand the importance of recovery, and helped her objectively re-learn what a recovery pace is.

Laura told me that going into her first marathon she was in fear of going out too fast. But she had enough physiological data that she could calculate what her heart rate should be for a marathon. So she ran that race, under control, listening to her heart rate. And it worked well for her! But now she knows her marathon body better, and does not tie her race to the monitor.

My conclusion is that if you are switching up your training, learning new paces, or intensities, or routines, it is a good, methodical, metric to help learn. But in the end your body learns the rhythms, which is really more important. In the end your body knows when you are in the right zone.

I think the analogy I want to use is to say it is like when you learn to play an instrument. You spend a lot of time playing the "scales" and "études" to find your way around what the instrument can do. When you advance, you may even use the scales and études to warm up. But that is not what you are going to play in your recital. By that time better music will be deeper ingrained in your spirit and you will know what is right.

You can use heart rate to tune your pace and train your body-mind connection. But in the end, you race from your heart and soul.